Structured Visions (Jodie Clark)

Explore every episode of Structured Visions

| Pub. Date | Title | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 06 Apr 2016 | Episode 39 The path of least relevance | 00:19:18 | |

Tumble dryers, the musical beat, computers, bodies, black holes, hairy black holes, information, desire, French laundromats, homeless soothsayers and Maya Angelou. Welcoming, adapting, embodied social structures. What more could you want from a Structured Visions podcast? | |||

| 08 Oct 2015 | Episode 13 Let's dance | 00:30:34 | |

Last week I talked about how bodies are disciplined to conform to societal norms. This week I discuss the pressure to conform to a consistent identity. I explore this idea in relation to two renowned scholarly figures – Michel Foucault and Monica from Friends. I get curious about how the enjoyment of the body might have the power to challenge or change social structures. And a young woman named Maryam takes to the dance floor to challenge narrow perceptions of identity. | |||

| 29 Jun 2023 | Episode 88 Grammar shame | 00:40:25 | |

What’s your most mortifying experience of grammar shaming? Mine involved a misplaced apostrophe in an important email, and I still burn with shame to think of it. Grammar for many has a spectrum of negative associations, which ranges from the imposter syndrome you might get when you realise you can’t tell a preposition from a conjunction to more serious and oppressive forms of linguistic prejudice. An example of the latter can be found in Geneva Smitherman’s account of her childhood experiences in her book Talkin That Talk. After her family moved from rural Tennessee to Detroit, Smitherman’s teachers decided that the way she spoke indicated a lack of intelligence and put her back a year in school. Later she was placed in speech therapy because the educators didn’t recognise her linguistic variety, African-American Vernacular English, as a legitimate form of English. Ann Phoenix’s work describes similar racism encountered by Afro-Caribbean children in British schools, who spoke perfectly grammatically in a variety that was not White enough for their teachers and peers. As I’ve written, ‘To be grammar shamed is to be told there’s something fundamentally wrong with the way you’ve expressed yourself. The implication is often that there’s something wrong with you: you’re not smart enough, you’re not well educated enough, you’re not savvy enough, you’re not “in the know,” you don’t have the right kind of cultural capital and/or you shouldn’t be taking up space on whatever platform you’re using.’ (Clark, 2023, pp. 5-6) The story I read in this episode, ‘Little red grammar hood’, hints at a deeper grammar, a welcoming grammar, one that is not shamed. Clues about such a grammar can be found through an exploration of what babies know about the grammar of the language that surrounds them, before they’ve even begun to speak themselves. In my forthcoming book, Refreshing Grammar: an easy-going guide for teachers, writers and other creative people, I offer ways to tap into what you’ve known about grammar since you were a little cutie pie. Before you even knew you knew it. Check out my new website, jodieclark.com, for information about Refreshing Grammar, the book, and Refreshing Grammar, the course. Prepare to be refreshed! Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! Works I discuss in the podcast Clark, J. (2023). Refreshing grammar: an easy-going guide for teachers, writers and other creative people. GFD. Naigles, L. R. (2002). Form is easy, meaning is hard: resolving a paradox in early child language. Cognition, 86(2), 157–199. Phoenix, A. (2009). De-colonising practices: negotiating narratives from racialised and gendered experiences of education. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 12(1), 101–114. Smitherman, G. (2000). Talkin that talk: language, culture, and education in African America. Routledge.

| |||

| 07 Jul 2016 | Episode 52 I’m very grateful for you listening today | 00:27:41 | |

Today I celebrate 52 weeks of religiously produced Structured Visions episodes! Enjoy a glass of bubbly with me while I share with you some of the motivations behind making the podcast and what I find so enjoyable about it. I also express my gratitude some figures who have been inspirations for me along the way: Tara Mohr, whose work on callings, and whose dedication to promoting women’s Playing Big made me recognise this way of honing my voice, exploring ideas on the public stage and ‘shipping’ my ideas (to use Seth Godin’s term). Elizabeth Gilbert, whose ideas about creativity I’ve found to be remarkably helpful in my academic career. In Big Magic, her book on creativity, she writes ‘I’ve always found like this is so cruel to your work – to demand a regular paycheck from it, as it creativity were a government job, or a trust fund’. This podcast has been my attempt to serve creativity rather than asking it to serve me. Caroline Casey of KPFA’s Visionary Activist Show, whose wisdom and enthusiasm are encapsulated in one oft-repeated quote: ‘Imagination lays the tracks for the reality train to follow.’ So many of my ideas are rooted in this principle – and I’m very grateful to Caroline Casey for giving such exuberant voice to her own ideas. And speaking of religiously producing podcasts, I’m grateful to Rob Bell for his RobCast, and for his appreciation for the art form of the sermon. I reveal in this episode how my own love of the sermon nearly led me down the route of religious vocation. Special thanks as well to Professor Sara Mills, Dr Liz Morrish, Dr Erika Darics and of course, my magnificent brother from the new world, Michael Clark – your retweets and comments are much appreciated! | |||

| 28 Dec 2023 | Episode 94 Language and the afterlife | 00:53:28 | |

What happens when we die? Ideas about the afterlife (or the lack of an afterlife) requires theory building based on either faith or experience. What if you don’t have faith in stories about the afterlife and you’ve never experienced anything resembling a near-death experience (NDE)? In this episode I’ll guide you through a language-based exercise that might help you with your theory building about worlds beyond everyday experience. The task is to ‘experience your world’, first through the filter of language and then without the filter of language. The intention is to open up the possibility that there are at least two different (simultaneous) worlds, layered on top of each other—at least two different dimensions of experience. If we accept that, why might there not be at least one more? Or even many, many more? The other thing that we might notice is how the filter of language presumes and produces a distinction between self and other, which disappears when we remove this filter. Because the linguistic dimension restricts us to the experience of selfhood, it might be the most constraining of all dimensions. And we can speculate about the existence of a soul that survives death and lives simultaneously in many (or all) dimensions. But before we get swept away in our excitement about this transcendent soul, we might allow ourselves to enjoy a certain fascination with living within a restrictive, linguistic existence and the creativity that might emerge from this level of constraint. The story I read in Episode 94 is ‘Moving language’. Sign up for the Grammar for dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Check out my new course: The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: Exploring the Emotional Depths. Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 31 Aug 2023 | Episode 90 Language, intimacy and narcissism | 00:42:59 | |

What’s the worst relationship you’ve ever been in? What’s the difference between this and that? There are at least three ways of understanding that second question, each of which reveals a different level of abstraction: metalinguistic, anaphoric and exophoric. Our exploration of this and that (proximal and distal demonstratives, that is) reveals the gift, the risk and the challenge of human language. The gift: Language creates selfhood, and with selfhood comes intimacy. The risk: Language can also create an obsession with the self, disavowal of the other, narcissism. The challenge: To recognise that our selfhood is a gift of our evolving human language, which is a gift of the evolving Earth. With language we’re offered the opportunity to recognise the limitations of the self, and to be open to the mystery of the other. The translation of the quote from Buddhist sutras about the finger pointing at the moon is from: Ho, Chien-Hsing (2008). The finger pointing toward the moon: a philosophical analysis of the Chinese Buddhist thought of reference. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 35 (1):159-177. https://philpapers.org/rec/CHITFP-2 Check out jodieclark.com for information about Refreshing Grammar, the book, and Refreshing Grammar, the course. Sign up for the Grammar for dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter | |||

| 17 Jul 2015 | Episode 1 The mystery of the little Black baby dolls | 00:19:16 | |

Welcome to the very first episode of the Structured Visions podcast! In this episode I look at aspects of racial injustice. I share some perspectives from my five-year-old self to show how certain logical structures enabled me to cope when I first noticed racial inequality. I talk more about what it means to understand racism, or any other form of social injustice, as structured. I invite listeners to start imagining new structures.

And I put forward this idea as a teaser:

Tune in to the next episode to hear more about grammar and the structure of social worlds. In this episode I mention Drs Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s doll test and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva‘s chapter in the book White Out, edited by Ashley W. Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. | |||

| 18 Aug 2015 | Episode 6: I was one of the those: uniqueness and community | 00:28:42 | |

I tell more stories about my experiences in Strasbourg and American students doing their best to fit in. Often fitting in to aspects of French culture, and learning French, was made difficult because of how much they enjoyed being in the company of other English-language speakers. Thinking about them as a ‘community of practice’ – a term coined by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger in their book, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation – helps us to understand that better. Lave and Wenger say that you learn particular skills by being part of a community committed to a particular activity, like baking or playing basketball. The students joined together to engage in the practice of learning French and learning about French culture. If they’d come to France to learn to be bakers, it might have been easier to learn French, because learning French would have been just one aspect of a bigger picture: being part of the community of bakers. ‘Communities of practice’ explains a lot, and it has been used in quite a lot of sociolinguistic research (including the work by Penelope Eckert and Mary Bucholtz I discussed last week). The idea is that identity has more to do with doing particular things than with being a particular way. Some things it might not explain, though, such as what it felt like for Cheryl Harris’s grandmother when she was passing as White in order to get a job that would support her family. It might not explain what I call

So I’ve decided to start exploring not just the models of community that scholars develop, but also the models of community that people come up with in their day to day conversations, even when they don’t realise it. Take this conversation between Mary and Rachel:

By using the demonstrative ‘those’, Mary is signalling that there is a category of people that she belongs to. Rather than telling us what qualities these people have, she acts them out for us by performing a little monologue about what they might say. She’s describing herself as unique from the other people in her Strasbourg community. That is, she’s different from them, but still recognisable, because she belongs to a category that others can understand. This act of dividing people into categories turns out to be a way of making it possible for Mary to be a unique individual in her community. This raises some issues/questions for me. Some quotes from the episode:

More next week on co-creating community through conversation, and the relationship between the individual and the community. | |||

| 02 Jun 2016 | Episode 47 The grammatical face of the other | 00:42:11 | |

We go back to middle school this week, looking once more at the This American Life episode dedicated to the subject, and taking up once again Levinas’s notions of alterity and face. Here’s what I said last week about middle school:

I also said this:

But how do you look at the face of the social body? How do you find its eyes, ears, nose and mouth? I propose in this episode that grammatical analysis gives us access to the otherness of the social body. In other words, grammatical structure is the face of the social body. For an example, consider what Ira Glass says in one segment of the middle school episode of This American Life. He’s talking about a seventh-grader’s experiences in the classroom. I’ve divided his comments into tone units, and underlined the noun phrases that serve as Themes (in some cases) and Subjects of clauses (in others): a big problem for him one reason that he was ostracized he didn’t wash kids would whisper about it and when he would get mad and then arguments would escalate that is where it would go. ‘You’re dirty.’ ‘You smell.’ The kids would say it right to his face. Where are the grammatical selves in this text? Note that there are two selves here: the unique, individualised, embodied, singular ‘he’ and the collective, plural, non-embodied ‘kids’. ‘He’ is the one with the ‘big problem’ – and what is his ‘big problem’? His body. It’s dirty, it smells, he doesn’t wash it. If this non-individualised collective, the ‘kids’, is the social body here, the social body is doing something we see it do often: it’s bullying the individual human body. What’s the possibility for transformation here? Well, seeing the social body configured in this way – that is, divided into the individual embodied self and the collective group self – opens the way for us to imagine a different configuration. What about one in which the collective were instead comprised of multiple unique, individual, embodied selves? And what if these human bodies were not seen as ‘problems’, but instead as singular, unique sites of new possibilities? | |||

| 13 Oct 2015 | Episode 14 Liza got hair: thwarting recognisability | 00:30:57 | |

How do you know if a social structure is having an impact on you? Have a look around and notice if there’s anything you recognise. If you’re using language to label the things in the room, for instance, you’re participating in a linguistic structure. A language structure is a social structure inasmuch as it is designed by and for the community that uses it. Also: how well do you recognise the people on the bus? If you can refer to ‘the old man’ or ‘the smelly woman’, you’re drawing upon a social structure that is organised around the qualities of age and smelliness. Recognisability is limiting if it keeps us from even seeing those things that are not already part of the social structure. For me truly open, welcoming and progressive social structures would be dynamic, and they would organise themselves on those things that we can’t yet recognise. I’m on the lookout for social structures that allow for new possibilities that might emerge from the unrecognisable. Some of those new possibilities present themselves to me in the form of a 6-year-old boy speaking up for his big sister. | |||

| 30 Nov 2023 | Episode 93 Where do you stop and the rest of the world begin? | 00:49:18 | |

Is there a distinction between you and the rest of the world? Where do you stop and the rest of the world begin? What’s the meaning of the word ‘now’? The gift of language is that it shapes and reshapes the experience of separateness. It’s a gift because it’s fluid. It’s more a membrane than a wall—with every utterance, there’s a new configuration of separateness. The gift of separateness is that it invites mystery. The word Carl Jung uses for this is numinous, which comes from the word numen, meaning divinity, god or spirit. Language gives you access to divinity. But it requires first that you disown the divine aspects of the self, so that you can experience the joy of reunion. The story I read in Episode 93 is ‘Salesman to the gods’. The other story I mention in ‘Ghosts’. Sign up for the Grammar for dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Check out my new course: The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: Exploring the Emotional Depths. Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 26 Sep 2024 | 103 Inhabiting language | 00:53:27 | |

In this episode I’ll try to convince you that using language to express the self is like a dog chasing its own tail… or a snake eating its tail, if you prefer ouroboros imagery. My perspective is that human language is the one-dimensional structure that shapes the self and thus limits access to the vast multidimensionality of consciousness. Language can’t refer to anything beyond itself (or beyond the self). The good news is, that when human language draws a circle that says ‘this is you,’ it creates a space that you can look inside. What you might find is not the you created by language, but instead the part of all the worlds that is uniquely designated by that self-circle. Transformation comes from truly inhabiting the space that language creates. On the journey of this episode we’ll be rambling through the realms of phrasal verbs, conceptual metaphor theory and the challenges of learning English as a second language. The blog post I mention in the episode is ‘What’s up?’ by Elaine Hodgson. The story I read is ‘The Museum of Language.’ Lots of things going on… Refreshing Grammar is open now (jodieclark.com/refreshingcourse), and will be free until 12 November 2024. You can get the unlimited access version for a very special, limited-time price here: jodieclark.com/rg-unlimited-access Also check out the amazing offer on my other amazing course, The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: jodieclark.com/SDT Come join me on 11 October at Off the Shelf Festival of words for a free, interactive online writing workshop, The Impossibility of Words: A Linguist’s Cure for Writer’s Block. Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter | |||

| 29 Oct 2015 | Episode 16 Blank boys and blank girls | 00:31:24 | |

I’ve been talking a lot about recognisability in social structures. Closed social structures divide up the world into particular categories such that it becomes impossible to think outside those categories. What doesn’t ‘fit’ within those categories, or identities, or ways of being, or ways of feeling are rejected, ignored or simply not allowed to exist. How might it become possible to think beyond the structures that structure thought? We’d have to think more than we can think. ‘A thought that thinks more than it thinks,’ writes philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, ‘is a desire’. To imagine new possibilities within a structure requires moving beyond thought, into a different realm of experience. But is it appropriate to call that realm of experience desire? Desire is a loaded term – just ask Banarama and U2. In fact, it is sexual desire that is at the heart of that compelling social structure in which human beings are divided into two – and only two – distinct groups: males and females. As part of this dividing practice comes the requirement that sexual desire only occur between the two groups, and not within them. This requirement starts early. Indeed, I remember participating in heterosexual matchup games – which boy do you like? which boy are you going to marry? which boy are you gonna chase on the playground? – from about the age of 5. How do social requirements about desire shape social structures? I share some discoveries from my ethnographic study of a women’s field hockey team (detailed in my book, Language, Sex and Social Structure). Anxious about the fact that there were lesbians on their team, the heterosexual women I spoke to made a point of distinguishing the hockey team from other university women’s teams, like rugby. There really aren’t that many lesbians in women’s hockey, I was told. Women’s rugby is where the real ‘problem’ is. One of the ways they depicted women’s rugby as a problem is by portraying rugby players as having desire for women. Hockey players might have sexual encounters with other women… but they don’t desire them (which by implication would mean they’re not really gay). Clearly a desire that is entirely shaped by a closed social structure isn’t really a desire at all – or is it? It’s certainly not the type of desire that Emmanuel Levinas was writing about. What would it be like to experience the Levinas form of desire: to think beyond the thinkable, to imagine new possibilities for being? | |||

| 14 Jan 2017 | Episode 58 Communities of Sara Mills | 00:30:59 | |

In this episode I share the talk I gave at the Symposium at Sheffield Hallam University on January 12, 2017, in honour of Professor Sara Mills’s retirement. Many thanks to all who participated in the event, including fellow speakers, Chris Christie, Lucy Jones, Shân Wareing and Karen Grainger. Special thanks to Dave Sayers and Alice Bell for organising such a moving tribute to Sara. Is there something you’d like me to discuss in an upcoming podcast? Get in touch! Click here to access the slides from the talk. | |||

| 03 Dec 2015 | Episode 21 Where are you? Who are you? | 00:30:54 | |

This week I question whether the notion of the ‘self’ is as stable as people seem to want it to be. The instability of the self might be explored in terms of how it is situated within the language system. What words do you use to refer to your self? You might use a pronoun, but which one? Me, I, my, mine, myself? It all depends on its position in the sentence. Also, using a pronoun is always unstable, because pronouns are deictic – that is, they change according to their context of use. The pronoun ‘I’ can mean Jodie Clark, Madonna, Henry IV or Kermit the Frog, depending on who’s speaking. You might use your name to refer to yourself, but names aren’t that stable either. Besides, try referring to yourself using your own name in a business meeting.

Why is this so weird? It’s because in the language system, the ‘self’ has its meaning only in relation to other selves – the self is not some stable entity with a fixed term of reference. If the meaning of the self in the language structure is relative, what about the meaning of the self in the social structure? To explore this question, I draw upon Michel Foucault’s work, which, he says, is oriented toward creating

‘Subject’ is a beautifully ambiguous word: it can mean the self, the subject of a sentence, or someone who is subject to another power, such as a monarch. Foucault was particularly interested in how it was possible for people to be subjected to power structures even in democratic societies. One way to do it, he argues, is to make people constantly obsessed with their selves, to make them feel the need to be constantly vigilant about their behaviour and how well they fit in to society. In his History of Sexuality, volume 1 he discusses how well the ‘confession’ works to make people self-monitor. The confession shows up, he argues, in many different contexts – it’s not just for church anymore. Once you confess to those behaviours, desires, thoughts and ways of being that are wrong, your self is safe and stable – it is welcomed back into the social structure that divides the world up into right and wrong desires, thoughts and ways of being. My own work, on the other hand, explores unsafe selves. I have the idea that it is those ‘selves’ that don’t fit in that carry with them the potential to transform social structures. | |||

| 24 Sep 2015 | Episode 11 I’m so fat and so short: the fragmented body | 00:32:45 | |

If you were in a position to make a judgement about someone – in a job interview, for instance – would you take into account what their body looked like? One widespread societal message is that the uniqueness, the individuality, the ‘personhood’ of a person has nothing to do with what their body looks like. Why is the idea that the ‘person’ or the ‘self’ is separate from the body so prevalent in our society? In this episode I put forward three possible reasons:

I analyse a conversation in which a young woman named Rachel recounts her experiences working in the plus-sized department of a women’s fashion retail store. Here’s how Rachel describes typical customers:

Rachel structures her account such that it is not individual women who are speaking, but a group of women united by shared bodily features: being women, being old, being fat. Notice that it’s OK to judge bodily features in a way that it’s not OK to judge a person for having those features. There’s a strong tendency to see the body as fragmented – divided up into parts, all of which can be separately judged. | |||

| 28 Apr 2022 | Episode 74 Create nothing | 00:53:38 | |

Is there anyone in your life who truly ‘gets’ you? What’s your favourite fairy tale? Have you ever received guidance from a wiser, more loving version of yourself? Believe it or not, there is a connection between all these questions. The first question came into the foreground for me when I first moved to Britain to do my PhD and was regularly doling out guidance to my student housemates. One of them was convinced that I ‘got’ her in a way her boyfriend didn’t. I didn’t have the heart to tell her I don’t think anyone ever truly ‘gets’ anyone else. Clearly ‘getting’ someone means to ‘understand’ them, but in the same way that you ‘get’ the punchline of a joke. To get a joke means that you have access to all the assumptions on which the joke is based. (In linguistics these are called implicatures.) But jokes are simple, and people are vast and complex. And you are not a joke. You are nothing less than a wild, mad-cap, unsolvable mystery. By definition, ungettable. But that doesn’t stop us from longing to be seen, understood, to feel held, to resonate with someone. To experience that beautiful sense of freedom that comes from not having to explain yourself. I believe that this longing, this loneliness, is part of the human condition, and I believe that what causes it is language. To illustrate this point, I’ve rewritten my favourite fairy tale, Rapunzel, in a story called ‘Longing’ (which is available on my Grammar for Dreamers blog grammarfordreamers.wordpress.com). According to my version of the story, the Earth once had a longing that only the Sorceress, Language, could fulfil. What could the Earth possibly long for? The natural world is governed by interconnection and symbiosis. How could it possibly be lonely? What if the Earth longs for longing itself? What if the Earth longs to experience the separateness that can only be experienced by a distinct, isolated self? In my version of the Rapunzel story, I have the Earth abandon one of its beloved creatures (human beings) to the one magical being that could provide that (language). Language creates the self. What the self creates is, precisely, nothing. If we see the self as a membrane (another of my favourite images), and when we look courageously at what’s inside that membrane, we see... nothing Nothing we can grasp, nothing we can ‘get’, nothing fathomable. Just a miraculously fertile void from which new ideas can emerge. And when those new ideas emerge, we are in the privileged position of seeing them as other. Like a magical doll in a fairy tale, or a wiser, more compassionate version of ourselves. The Self and the Other allow us to experience mystery. And through us, the Earth can experience mystery as well.

Check out my free course, ‘Writing through the Lens of Language’: bit.ly/lensoflanguage Join my Patreon community for more linguistic inspiration: https://www.patreon.com/jodieclark Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 29 Nov 2022 | Episode 81 What are your pronouns? | 00:47:03 | |

‘What are your pronouns?’ How often do you get asked that question? How does it make you feel to be asked? When did the question first start making sense to you? This episode explores the ways that pronoun usage has shifted over time to reflect new ways of thinking about the relationship between self and society. We’ll draw upon Brown and Gilman’s seminal essay, ‘The pronouns of power and solidarity’. And we’ll go back to Girl Scout camp in the early eighties, which is where my real education in pronouns began. The story I read in this episode is ‘Of prophets and pronouns’, available on grammarfordreamers.com. Take my free course, sign up for my newsletter, get my screenplay—do all the things, here: grammarfordreamers.com/connect Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 04 Aug 2016 | Episode 55 Critical condition | 00:27:55 | |

This week I discuss the branch of linguistics – Critical Discourse Analysis, or CDA – that most informs my approach to grammatically analysing texts. It’s the ‘critical’ part of CDA that appeals to me most – an aim of most practitioners of CDA is to explore the role language plays in maintaining or challenging social injustices. To give you an idea of how CDA usually works, I analyse a recent news item from Fox News. (Click on the headline below for the full article.)

Doing CDA requires being explicit about what critical position you’re coming from when you interpret the text. The position I bring to my analysis of this piece is a feminist one. I put forward my view that the article (a) downplays the structural inequities in an institution in which there is a phenomenal gender gap and (b) draws implicitly upon the assumption that such inequities are ‘natural’, or to be expected. The grammatical analysis of conversational texts that you’ve heard me do in these podcasts, though, is different from ‘traditional’ CDA in an important way. In CDA, the text is seen as an end product, and CDA explores the processes by which the text came into being. CDA is rooted in Marxist thought, and an analogy is helpful here. A Marxist perspective on a garment in a department store might raise questions like, what were the conditions under which this piece of clothing was manufactured, and how does it come to be priced so low? What workers were involved in producing this item? Were they treated fairly? How were the paid for their labour? A t-shirt is seen as the end of a long line of manufacturing process, and exploring those processes is likely to reveal systemic social injustices. Similarly, Critical Discourse Analysts view a text as a product of a set of language processes that involve construing reality in a particular way and drawing upon assumptions that mask damaging ideologies about the social world. It can get a little depressing. How is my own work different? I too, start from the position that social injustices structure the social world, and I too, want to do something about it. But rather than assuming that the text is the ‘end product’ and going backwards to look at the processes of its construction, I assume that the text is a ‘midpoint’. The work I do is looks forward, not back. My idea is that the analysis of the grammar of a text can generate new possibilities for more welcoming, inclusive social structures. If CDA reveals the sinister secrets hidden in the production of a text, my work reveals the germs of new, transformative ideas that I believe are also hidden there. This perspective requires a radical new look at language and society. Join me in an upcoming podcast for more! | |||

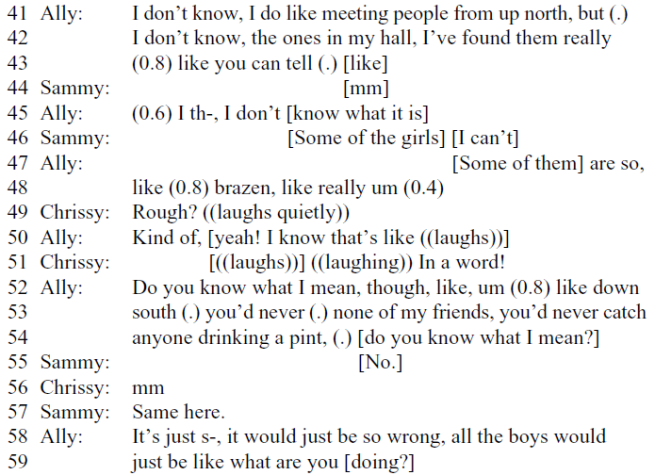

| 24 Mar 2016 | Episode 37 Sand in my teeth | 00:29:52 | |

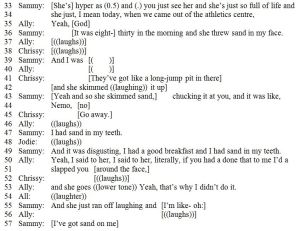

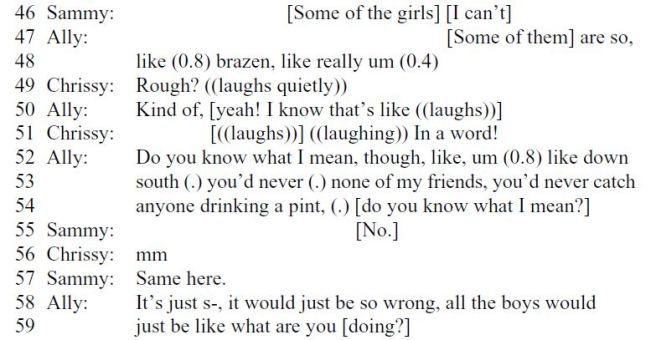

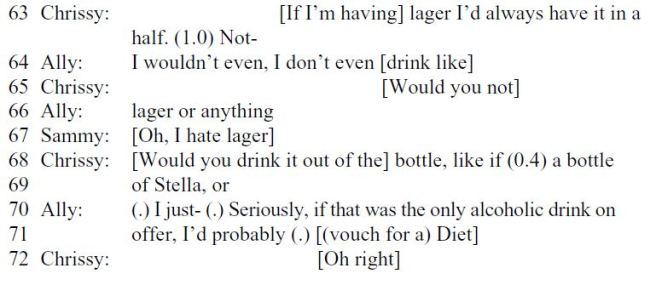

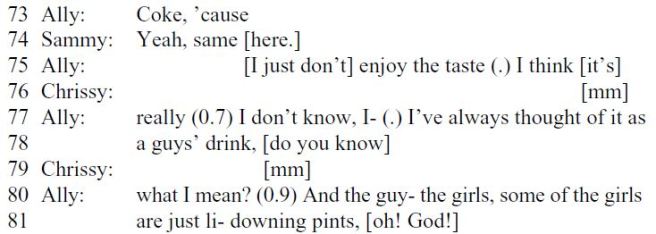

I’m still dreaming, in this episode, of a society in which unique selves are possible. Such a dream goes beyond ideas about social inclusion. Inclusion is about fitting in to a pre-existing system – with all the rules and prescriptions such a system holds. My vision is of a social structure that welcomes uniqueness, indeed, one that expects uniqueness, that allows itself to be transformed by each expression of a unique self. Such a vision makes me dubious about all the imagery that’s been showing up in these podcasts. Comparing social structure to computer codes and choose-your-own-adventure novels makes it seem like the selves society constructs are all decided in advance, which furthers the idea of social structure as a closed system. I also start to become a bit suspicious of the personified Society I keep talking to. Despite its claims to the contrary, I’m certain Society is perfectly capable of making space for unique selves. If I’m going to keep this dialogue going, I’m going to have to be more cunning in my cross-examination. I draw inspiration from – where else? – Reese Witherspoon’s performance in the court scene of Legally Blonde. Like Witherspoon’s character, Elle, I’m going to have to catch Society in the act of making space for a unique self, even when making space takes the form of an attempt at exclusion. I get my chance through an analysis of a conversation between three first-year university students, teammates on a field hockey team. Read the transcript and see if you notice anything about the selves that show up in the grammar of Sammy’s story: Now have a look at the clauses of the narrative that are only Sammy’s:

Did you notice the shifts in Sammy’s story between the impersonal selves (the generic second person in clause 5, the impersonal dummy subject in clause 6), and the individual selves (such as the first-person singular and the third-person female singular in clauses 3 and 10)? What I find so interesting here is that the unique, individual selves show up – because they have to – whenever the body comes into the picture. It’s not possible, in other words, to throw sand into an impersonal, non-individualised face. It’s also pretty hard to imagine impersonal, non-individualised sandy teeth. When unique selves show up, they’re represented as embodied. It’s no good, then, thinking of social structure in terms of something disembodied, like computer code. We need a new metaphor for social structure. Maybe by next podcast we’ll have one. My analysis of this extract comes from my forthcoming book with Palgrave: Selves, Bodies and the Grammar of Social Worlds. | |||

| 30 Sep 2015 | Episode 12 Foucault, the panopticon and the tyranny of cartwheels | 00:32:19 | |

We’re still talking about bodies but this week the focus is on how they’re disciplined. I explain some of the ideas in Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish. An important component of Foucault’s work is the mechanisms that keep societal structures in place. In a feudal society, structured hierarchically according to the birthright of the royalty and the landed gentry (and the lack of birthright of the peasantry), social structures stayed in place through a collective belief in the power of the king. If ever the king’s power was threatened through a usurpation attempt or an enemy invasion, some public and gory displays of ritual torture would remind everyone of how powerful the king was. After the French Revolution and the subsequent removal of the aristocracy, power takes on a different form. People now have power not by virtue of birthright, but according to how much money they have or how many valuable goods they have accrued. This measure of power is less stable and more vulnerable – because what’s to stop other people from simply stealing your stuff and thus having more power than you? According to Foucault, a new disciplinary system needed to be put in place in post-Revolution France, whereby individuals had to be convinced they were members of a social contract, and that they had to obey the rules of that contract. Laws became codes that served as reminders of the contract. In addition, a capitalist economy required the generation of more goods and resources, and human bodies became seen as powerhouses that could be exploited in factories and workhouses to produce more goods. The best way to control individual bodies, Foucault explains, is through convincing them to self regulate, to worry about how well they’re measuring up and how well they’re conforming to the demands of the system. Foucault illustrates this principle through his description of a type of prison called the ‘panopticon’. I illustrate the principle through a story about trying to train my 9-year-old body to do cartwheels the length of the floor of a school gymnasium – and the shame I felt when such a feat proved impossible. The impulse – produced in a ‘disciplinary society’ – to self regulate encourages us to fixate and obsess about our individual selves and how well we’re measuring up. There is little incentive to look at the bigger picture and ask questions about the societal structure that requires such oppressive self regulation. In this episode I ask: How might society be structured such that a different relationship between self and body were encouraged? Imagine a social structure, for instance, in which individuals were welcome to enjoy the experiences their bodies offer. What if society shaped itself around the joy of embodied experience? That’s an idea worth thinking about. More on that next week. | |||

| 07 Jul 2016 | Episode 53 Submerged in the social world | 00:23:05 | |

Remember Episode 51, when we made our way, blindfolded, around a room with nothing more than a cardboard tube to guide us? We delve deeper into the depths of phenomenology this week – almost literally – taking seriously Sara Ahmed’s description in her Queer Phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty’s perspective, in which ‘bodies are submerged, such that they become the space they inhabit’ (Ahmed 2006, p. 53). Ahmed’s critique encourages us to reorient our phenomenologies, to understand the spaces in terms not only of what is oriented to, but also in terms of what is backgrounded, what is beyond reach for certain bodies. My own perspective on phenomenology is this: yes, consciousness is always embodied, and bodies are always submerged. But let us not assume that consciousness is embodied in human bodies and that these bodies are submerged in the material world. My take on human bodies and the material world is that these are always just beyond our reach – that consciousness rarely attaches itself to the human body, and that the human body and the material world are both inevitably other. My idea is that consciousness instead attaches itself to a social body. Whether we navigate a room blindfolded with a cardboard tube to guide us or manipulate the perceptual field with our gaze, it is almost always a social world we are submerged in, and it is almost always a social body that our consciousness affixes itself to. | |||

| 29 Jun 2024 | Episode 100 Selfish wishes for social change | 00:45:23 | |

What are your top three wishes? Are they selfish? As it happens, your wishes may be worse than selfish—they may be toxically self-effacing. If you participate, on whatever level, in a society in which people are continually and oppressively bullied into thinking they need to be someone other than who they are, then you may be wishing for things that obliterate your own unique selfhood. In this episode we explore the linguistics of wishing—with a close look at realis and irrealis expressions—and discover what grammatical structures can reveal about a desire for a transformative society. We explore the possibility of a social structure in which individual selfhood is protected and sustained by a mutually supporting community. The book I refer to in this episode is Selves, bodies and the grammar of social worlds, and you can learn more about the analysis I did there in Episode 58, ‘Communities of Sara Mills’. The stories I read in this episode are ‘Beyond desire’ and ‘Ala’s lamp.’ Connect with me and discover my courses on jodieclark.com Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 26 May 2022 | Episode 75 Accidentally born again | 00:58:24 | |

What’s your relationship to religion? This could be a tricky question, for lots of reasons. People may not understand your faith. People may not understand how your faith is connected to your culture. People may not understand why you aren’t part of a religion. Maybe your experiences of religion have been traumatic in some way. To make this topic a little more light-hearted, it might be best to start with a different question. What’s your most embarrassing religious moment? Here’s mine: I accidentally became a born-again Christian at the age of 12. In this episode we explore my hapless conversion in more detail. We gain some perspective from a book called The elementary forms of religious life, written by French sociologist Emile Durkheim. In Durkheim’s analysis of what’s at the root of all religions, he draws these conclusions:

These conclusions are a little hard to swallow, particularly because we live in a moment where we’re right to be critical of society and the roles it establishes for us. Especially as these roles are carved out of endemic structural injustices. But why do human beings need to actively connect with something bigger than themselves? It seems to me we’re already connected to something bigger than us—the natural world. When I imagine the natural world as a conscious entity—and it’s one of the themes I love to explore in my fiction—it makes me feel like I am already part of a bigger picture. This is true for me even though I feel separate from the natural world, even though I feel my experience is limited by the constraints of my language and my society. The idea I most like to play with in my fiction is that the human experience of separation from the natural world is not a flaw, but a design principle. I explore this notion in most recent story, ‘First words’, which is available on my Grammar for Dreamers blog grammarfordreamers.wordpress.com. I intended the ‘Seer’ character to be an agent of the natural world, creating language to produce the experience of separation, the concept of the self. The idea is that those of us who believe we inhabit selves (e.g. human beings!) are the routes by which the Earth itself experiences new ideas.

Intrigued? Would you like some more ideas about on how to tap into these insights on language and the self? Check out my free course, ‘Writing through the Lens of Language’: bit.ly/lensoflanguage Join my Patreon community for more linguistic inspiration: https://www.patreon.com/jodieclark Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 10 Jul 2016 | Episode 54 I was so hungry | 00:35:39 | |

Our explorations in phenomenology have led us to understand consciousness as submerged in the world of perception. I have made a case for understanding this phenomenological world not as material world, but as a social world. I keep drawing upon Merleau-Ponty’s image of the blindfolded person who uses a stick to gain perceptual experience of the objects in a darkened room. In today’s episode I play with the idea that it is language, or grammar, that serves as the ‘stick’ by which social bodies move through and perceive the social world. The episode moves from green coffee cups (not coffee green cups) to those blue suitcases, to the mainstream three pretty girls in a young woman’s account of being bullied at school. It’s the personal account that’s most important. My favourite way to explore the structure of the social body/world is to go megalocal: to examine personal, intimate accounts of people’s felt sense of belonging or not belonging. Here’s a transcript of Maryam’s account:  (click to enlarge) (click to enlarge)  (click to enlarge) (click to enlarge) | |||

| 28 Jan 2016 | Episode 29 Class(room) struggle | 00:34:04 | |

Is the individual determined by society? Or is the individual an autonomous actor, making the most of structural resources to navigate through society? These questions are familiar to Structured Visions listeners, but this week I attempt to make the debate a little less abstract. I replace the notion of ‘society’ with the image of the classroom, and the ‘individual’ with anyone who’s ever told a story about entering into one. I use these stories to suggest a third way of understanding the individual in relation to society. Let’s personify both entities to produce characters in a drama, I say. And let’s see these characters as co-constituting, co-creating reality. Better yet, let’s envisage this relationship through the metaphor of a bar magnet surrounding by iron filings. The individual ‘magnetises’ the components of social structure, such that they form a pattern around the individual. How about that for a promising metaphor? | |||

| 31 Aug 2022 | Episode 78 Love, language, music and aliens | 01:00:42 | |

Have you ever been in love? And if you could send a message to outer space, what message would it be? We’ll use these questions to guide us through an exploration of the evolution of language, music, intimacy and transformation. The book I discuss in this episode is Steven Mithen’s The singing Neanderthals: The origins of music, language, mind and body. The story I read in this episode is ‘Messages’, available on grammarfordreamers.com. Take my free course, ‘Writing through the Lens of Language’, to explore the experiential aspects of ‘inhabiting language’ in more detail: bit.ly/lensoflanguage Join my Patreon community for more linguistic inspiration: https://www.patreon.com/jodieclark Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 13 Apr 2016 | Episode 40 Discipline and Punish, part 1 | 00:35:21 | |

The first few pages of Michel Foucault’s book, Discipline and Punish, describe (in gory detail) a ritual execution from pre-Revolutionary France. I tend to be very squeamish about these things, so it’s a miracle I kept reading. Somehow I did, and in this episode I describe what it is in this book that inspires me. It’s not just that Foucault uses what has become my favourite metaphor – the image of social structure as a body – but also that he makes it possible to conceive of the social body as in relationship with human bodies. This image has been a springboard for my own ideas – a jumping off place where I can start imagining new social structures – more open, inviting, welcoming ones. That said, there’s an important difference between Foucault’s views and mine. Foucault’s image of the social body shows it as antagonistic toward the human body. The social body is always the bully, scaring the lights out of the human body in the same way that Tiffany Wood terrified me when I was five. In pre-Revolutionary France, for instance, the social body took the form of the reigning monarch, and it displayed its power over human bodies through ritual torture and execution. Luckily, Tiffany never went to those kinds of extremes. It’s hard to disagree with the idea that the social body bullies the human body. If you’ve ever felt guilty about something you should be doing, you have a good idea of one way that type of bullying operates – it’s an example of what Foucault calls ‘disciplinary techniques’ of power. However, I have a new way of thinking about the relationship between the social body and the human body. I propose that the human body has the power to transform the social body. Yes, the social body might understand the human body as a threat. But the human body only need be a threat if the social body is averse to transformation. My idea it that if the social body were ready to change, the human body has the power to transform it. Anybody wanna play with that idea for a while? Read my forthcoming book with Palgrave to learn more about what I’ve taken from Discipline and Punish: Selves, Bodies and the Grammar of Social Worlds. | |||

| 23 Feb 2023 | Episode 84 Language before language | 00:40:56 | |

Where’s home? What’s your first language? What was your language before your first language? Join me to explore linguistic frames of reference in Guugu Yimithirr, polyglot newborns and the beauty and tyranny of language, self and home. The story I read in this episode is ‘Poor Magellan’, and it’s available on grammarfordreamers.com. Connect with me (and sign up to my newsletter) here: grammarfordreamers.com/connect Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 29 Aug 2024 | Episode 102 How to belong | 01:09:41 | |

Have you ever felt like you don’t belong? My own red thread through the labyrinth of linguistics has been the theme of not belonging. We explore the grammatical shape belonging takes in everyday conversations about fitting in. We discuss how selves can grammatically ‘detach’ from bodies, and the transformative possibility of embodied selves. Join me in a hopeful dream where humans belong on planet Earth. We’ll explore how human language, which seems to divide us from wider consciousness, might be re-envisioned as an invitation to co-creation with the Earth itself. The story I read is ‘The last stage of the Earth’s evolution.’ I also mentioned my story ‘Summers with Mad Gran.’ Connect with me on jodieclark.com. Refreshing Grammar begins on 16 September 2024. Sign up here: jodieclark.com/refreshingcourse Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 02 Sep 2015 | Episode 8 The Model Person: traffic, politeness, French kissing and fingernails | 00:31:15 | |

In the past two episodes, I’ve been talking about how society needs to be structured in order for particular types of individuality to exist. In this episode I discuss two types of social structure: the system of traffic laws and culturally specific politeness norms. My interest in traffic laws comes from spending lots of time as a young girl annoying my parents while they were driving. My interest in politeness comes from having lived in a few different cultures and getting things very very wrong (like slamming my jaw into the cheekbones of complete strangers). Legal systems in most societies are based upon the principle of rationality: laws dictate what is the most rational choice so that people are compelled to make that choice or face unpleasant consequences. When someone breaks the law, they are usually held to a standard of rationality: they are judged according to what a rational person would do. If people were rational – and only rational – would we need politeness norms? Politeness norms are based upon the principle that other people might be offended by our behaviours. But why would rational people be offended? In their seminal work on linguistic politeness theory, Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage, Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson argue that politeness behaviour is not irrational. They based their theory on the idea that people are rational, but that they also have something called face. Face is the thing that keeps people from stating what they want in a straightforward way. Rather than ‘You there. Wrap this plaster around my finger so the nail stays in place’, they might say something like, ‘I’m so terribly sorry, I know this is very cheeky, but can I ask a big favour of you? Would you be willing to help me out? I know you’re in a rush….’ etc. To use a politeness strategy that attends to negative face, acknowledge that the person they’re talking to would rather be left alone, as in the example above. To attend to positive face, make the person you need help from feel like they’re just like you – part of a select group of people, as in ‘Help a fellow Goth?’ Whereas the legal system relies upon the notion of the rational or the reasonable person, the politeness system (at least as described by Brown and Levinson) relies upon the notion of the ‘Model Person’ – someone who has both rationality and face. I bring these notions up here because I want to explore the idea that these two types of system create a notion of a particular type of individual – an individual whose uniqueness has been stripped away and who is strangely disembodied. Next week I’ll discuss how difficult it is for some social systems to theorise in terms of individuals with bodies. For more on Linguistic Politeness, check out the Linguistic Politeness Research Group. | |||

| 29 Jul 2021 | Episode 65 Psychedelic linguistics | 00:44:15 | |

Have you ever repeated a word over and over again to yourself to experience the dissolution of its meaning? What if you were to do that with the word ‘me’? When I was a little kid, repeating the word ‘me’ became a doorway to a world where I was freed from the self that language had created. It was trippy. In this episode we’ll discuss the role of language in creating, dissolving and protecting selves. In my academic research I analyse transcripts of conversations to identify the shape of the social structure that emerges from people talking about everyday experiences. I look for grammatical patterns in the transcripts, asking these questions:

One transformative possibility that has emerged from this type of analysis is that selves need to be protected. Can language protect them? Think about the work you own name does in constructing your social self. But an anthropological look at naming systems makes it clear that names are less about protecting selfhood, and more about establishing someone’s place in a social structure. Even the seemingly ordinary principle that there are girls’ names for girls and boys’ names for boys, for instance, lets us know that we live in a culture that positions us in a binary gender structure. Having an established place in a social structure is not the same as knowing that your self is protected, revered, cherished. In my short story, ‘The Greenhouse’, I explore the idea that everything in the natural world has its own blueprint. – its chemical makeup, its DNA signature, etc. Everything in the natural world has something you could call a ‘name’. Or even a ‘self’. The ‘selves’ are in relationship with each other – molecules combine to form new molecules, membranes form that allow life to emerge What if the earth were to grant to one of its species the ability to play with these relationship-forming tools? What if human beings were offered a device to do creativity in exactly the same way the earth does creativity? Well so far, such a device has created social structures that produce division, hierarchy and exclusion. But there’s hope to be found in the etymology of the word ‘culture’. Culture is what we cultivate. Language is what we use to cultivate. To make a more welcoming social structure, let’s cultivate selves that felt safe and protected, that are crucibles for creation. Let’s use language to form linguistic membranes around selves, create spaces for new experiences, feelings, thoughts and ideas to emerge. *You can listen to me talk about this in more detail in Episode 58, which is a recording of the talk I gave at Sheffield Hallam University in 2017 in honour of Professor Sara Mills’s retirement. For an even more detailed version, have a look at my book, Selves, bodies and the grammar of social worlds. Are you enjoying these episodes? Would you like to hear more? Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google podcasts, or wherever you like to listen. For additional content: Subscribe to the monthly Grammar for Dreamers newsletter (and get a copy of the Grammar for Dreamers screenplay). Follow me on Instagram, where I regularly post videos sharing bits of linguistic geekery that delight me: @grammarfordreamers | |||

| 23 Dec 2015 | Episode 24 The Gift | 00:31:04 | |

A story of a Christmas miracle involving a pink Huffy Sweet Thunder bicycle leads to a discussion of whether Santa Claus is a social fact. According to French anthropologists Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, ‘social facts’ are those forces that maintain the integrity of societies – forces that transcend the needs and desires of the individual and require people to support the collective. One of Mauss’s examples in his essay, The Gift, is of the kula of the peoples of the Trobriand Islands in Melanesia. The kula is an elaborate ritualised exchange of two types of object: mwali (carved bracelets) and soulava (mother-of-pearl necklaces). The kula produces a set of obligations for the societies in the Trobriand archipelago: the obligation to give these gifts, the obligation to receive them, and the obligation to pass them on to a third party. These are not mechanistic exchanges: the objects themselves become imbued with magical significance, attributes, names, ‘personalities’. Maybe the obligation a father feels when his little girls ask a magical person – Santa – for a magical, but impossible-to-get toy unicorn also counts as a social fact? For Mauss and Durkheim, the point was to develop a science of the social world which would make it possible to investigate, objectively, those forces that hold societies, collectives and groups together. I propose a new way of doing social science. Rather than looking at the social facts as they are, I propose that we look to the social world for evidence in everyday conversations, of people’s desires for different types of social world. A social science that looks to ‘real-world’ evidence for ideas about alternative social structures that don’t yet exist? That, to me, would be a gift. | |||

| 30 May 2024 | Episode 99 Linguistics and astrology | 00:55:28 | |

What new language would you most like to know? Is astrology on your list? Does astrology count as a language? Maybe the language of the stars could be classified as a pidgin, a language without native speakers. But if, as discussed in Episode 96, ‘The Earth’s language’, languages are ways of organising information, then it might be more accurate to describe astrology as one of the Earth’s languages. If the Earth has a language, it’s using it to tell us:

Get your birth chart on astro.com. The story I read in this episode is ‘Pidgin.’ Connect with me and discover my courses on jodieclark.com Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 30 Jan 2025 | 105 Given, new and the selfless know-it-all | 00:53:31 | |

What if you could know everything, but you had to lose your self in the process? We discuss two layered structures in human languages. The first is word order, such as Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) and Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). The second is information structure, which is the system by which people in interaction navigate their interlocutor’s knowledge state, orienting what they say to make a distinction between given and new information. All human languages start from the assumption that human beings in interaction know different things, or are putting their attention to different things. In this episode we play with the idea that individual minds, with different states of knowledge, didn’t precede, but are produced by language. We pose the hypothesis that human language shapes the experience of selfhood—which therefore restricts our capacity to know everything. We also talk about Ted Chiang’s brilliant novella, The story of your life. But if you want to know what will happen in the future, you’re out of luck, because the future is a projection of the self, moving in a linear way through time. What are your thoughts about the ideas discussed in this episode? Because I have a self, I can’t know until you tell me. The story I read in this episode is ‘The dark art of world-building.’ Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 30 Sep 2021 | Episode 67 Imperative blessings | 00:50:53 | |

When did you learn that the earth travels round the sun and not the other way round? And when you talk to yourself, which one of the dialoguing characters is you? Language generates multiple selves, and each self comes with its own built in worldview. Is it superstitious to think of selves that are wiser than us, that are protective, that wish to bless us? Perhaps it’s reckless not to. The story I discuss in this episode is called ‘Go’. It’s just been published in the Running Wild Anthology of Stories, vol 5. I learned about imperatives in Omotic languages from reading work by Alexandra Aikhenvald. (See reference list below.) And the discussion of postmodernism is based on the following quote from Madan Sarup’s book, Identity, culture and the postmodern world: ‘Copernicus, Darwin, Marx and Freud have all, in their different ways, decentred the human subject. By “decentering”, I mean that individual consciousness can no longer be seen as the origin of meaning, knowledge and action.’ (Sarup, 1996, p. 46) References Aikhenvald, A. (2010). Imperatives and commands. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sarup, M. (1996). Identity, culture and the postmodern world. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. For additional content: Subscribe to the monthly Grammar for Dreamers newsletter (and get a copy of the Grammar for Dreamers screenplay). To watch my regularly posted videos of linguistic geekery, follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers or on Facebook: www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ Are you enjoying these episodes? Would you like to hear more? Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google podcasts, or wherever you like to listen. | |||

| 26 May 2016 | Episode 46 Middle school, embodied | 00:34:12 | |

In an episode of This American Life, 14-year-old Annie relates middle school to a ‘whitewashed, brick-walled, iron-gated prison’ that she finally escapes from. Annie’s description gives us a good excuse to revisit the use of prison metaphors to describe oppressive social structures. Foucault’s Panopticon will spring to mind for many Structured Visions listeners, but we don’t have to rely upon French social theory to find prison imagery applied to the social world. What Annie doesn’t do is compare middle school to a body. Human bodies are mentioned several times in the show – Alex Blumberg, for instance, describes middle schoolers as having to learn ‘how their bodies are now working’, and other guests describe ‘raging hormones’. But middle school as a social body doesn’t enter into the repertoire of metaphors. Middle school is understood as a prison or a ‘social order’, but not as a body. But you may remember that I’ve argued that the social body isn’t merely a metaphor, it’s a real thing. What is reality? we ask each other, trying to remember what we learned in undergraduate philosophy classes. After exploring where there’s any ontological basis for the social body, I conclude that we need less ontology and more alterity (otherness) – and we look to Emmanuel Levinas for guidance. If ontological questions are a matter of philosophical debate, alterity – a relationship with the other – is a matter of ethical responsibility. For Levinas, the image of the encounter with the other is the face: when we come into relationship with the face of the other, we have the opportunity to encounter worlds beyond those that we currently have the power to perceive, know or understand. The reason why I say middle school and other social structures are social bodies is because bodies have faces. Coming face-to-face with the social body of middle school – or any other social structure – makes it possible to for us to enter into new worlds, beyond our current understandings, and to be surprised, challenged and delighted by what we may see there. | |||

| 31 Jan 2024 | Episode 95 Your name without language | 00:50:38 | |

What would your name be without language? In this episode we explore the problem of names in truth conditional semantics, with a look at Gottlob Frege’s explanation of sense and reference, Bertrand Russell’s claims about the definite descriptors and Saul Kripke’s term for proper names, which is ‘rigid designators’. What would it be like if you weren’t so rigidly designated? Truth conditional semantics is concerned with making true or false statements about the world. But what if the world and language are on two different planes of existence? What if language is a one-dimensional phenomenon attempting to delineate multidimensional experience? The most fascinating aspects of language (to me) is that it presumes and thereby constructs a self. But a one-dimensional language, it would seem, would produce very limited, superficial selves. Does inhabiting language keep us from experiencing the vastness of other dimensions? (If this question sounds familiar, you might be remembering playing with it in Episode 94, Language and the Afterlife.) It turns out that the linearity of language offers possibilities not available in other dimensions. Language, being one-dimensional, can (and does) shape itself in constantly changing ways to create new selves. The selves form spaces from which new ideas can emerge. The story I read in Episode 95 is ‘The brutal linearity of language’. Sign up for the Grammar for dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Check out my course: The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: Exploring the Emotional Depths. Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 24 Feb 2022 | Episode 72 Apocalypse fantasies | 00:54:05 | |

Have you ever entertained an apocalypse fantasy? The one I invented relieves humanity of its language. Language produces selves, which is not a bad thing. It’s a beautiful thing. It’s the window to intimacy. But what happens when the amount of language we use increases to the extent that we’ve seen in recent years? The production of selves increases to potentially catastrophic proportions. Here’s the link to Dr Debbie Reese’s excellent critique of Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins: https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2016/06/a-critical-look-at-odells-island-of.html The book that inspired my fascination with mycelium is Paul Stamets’s Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Save the World. The stories I discuss in this episode, ‘Finite’ and ‘A remarkable outcome’ are both available on my Grammar for Dreamers blog: grammarfordreamers.wordpress.com Check out my free course, ‘Writing through the Lens of Language’: bit.ly/lensoflanguage Join my freshly minted Patreon community for more linguistic inspiration: https://www.patreon.com/jodieclark Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 31 Oct 2024 | 104 Consciousness is more than just a little cutie pie | 00:55:43 | |

Do human beings have more or less consciousness than the rest of the living world? Is language an addiction? We’ll explore both points by examining the relationship between language and time. To participate in the world of human language, we have to reduce ourselves to little cutie pies known as ‘selves,’ who exist at a precise moment of time and who orient to their world in relation to their deictic centre. What might it look like if we could see beyond the linearity of language and thus, the linearity of time? The story I read in this episode is ‘The end.’ Some time sensitive things to act on now: Refreshing Grammar (jodieclark.com/refreshingcourse) will be free until 12 November 2024. You can get the unlimited access version for a very special, limited-time price here: jodieclark.com/rg-unlimited-access Also check out the amazing offer on my other amazing course, The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: jodieclark.com/SDT Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 25 Oct 2023 | Episode 92 The grammatical shape of emotions | 00:39:55 | |

When was the last time you lost language? And… how do you feel? The one time it feels like I’m losing language is when I let myself feel what I really feel. (We’re talking about weeping, wailing, keening—the dripping-nose ugly cry.) I’ve been thinking a lot about emotions and language because I’ve just made a new course available, The Grammar of Show Don’t Tell: Exploring the Emotional Depths. It’s a love letter to my young writing self, who had no idea how to put ‘show don’t tell’ into my writing practice. In designing the course, I discovered the ways that writers grammatically shape their characters’ emotions. I look specifically at fear, envy, grief, love at first sight, sensuality and rage. In this episode we explore sorrow as a felt experience with a grammatical shape. (Ugly crying entirely optional.) The story I read in Episode 92 is ‘Death of a grammarian’. Sign up for the Grammar for dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 28 Nov 2024 | One from the archives: How linguistics can save the world (Episode 60) | 00:39:58 | |

I’m taking a short break from podcasting as I finish off the book I’m writing, but I’ll be back in the New Year. In the meantime, please enjoy this episode from the Structured Visions archives. Episode 60, How linguistics can save the world, originally aired on June 1, 2018. This podcast has been an amazing way for me to develop some unusual ideas about language. Recently I was wondering when I first came up with the idea that the Earth has its own language of which human language is one small but significant part. Episode 60 is one of the early recordings of me fleshing out that idea. I hope you enjoy it! Learn more about my ideas about the mysteries of language at jodieclark.com. Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here. | |||

| 28 Mar 2024 | Episode 97 The intimacy of denial | 00:59:30 | |

What’s the weirdest thing about human language? We explore linguistic polarity and all its bizarre implications. Embedded in every human grammar is a way of turning a positive clause (I’m listening) into a negative clause (I’m not listening). Grammatical negation is one of the ways we can do denial. (‘I’m not scared of that dog,’ said the three-year-old whose body was telling an entirely different story.) What would a language without negation look like? My story ‘Negative space’ refers to an (imaginary?) alien language where everything is expressed in the affirmative. Closer to home, we could speculate about the Earth’s own language. If languages are ways of structuring information, then human languages are uniquely structured around selfhood. Negative polarity works to structure the relationship between self and other, which sometimes means denying the other, sometimes affirming them. Either way it’s a route to intimacy. If human language draws a boundary or a membrane around the distinct self, then the intimacy of negation can be a way of acknowledging and celebrating those boundaries. The other story I mention in this episode is ‘Lessons in Latin’. Connect with me and discover my courses on jodieclark.com Sign up for the Grammar for Dreamers newsletter here: jodieclark.com/newsletter Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 28 Oct 2021 | Episode 68 Life, language and other mysteries | 00:46:26 | |

In this episode we’re going to address three questions. What’s a word? What was did it feel like when life first emerged on the Earth? When’s the first (or the last) time you made a real decision? And I’m going to try to convince you that these questions all have something to do with each other. I believe that thinking about words will give us a bit of insight about what it was like when life first emerged on the Earth. These two things – life and language – for me share two qualities: that they’re both incredibly commonplace, and they’re both overwhelmingly mysterious. Also, both require boundary making, whether that takes the form of a cell membrane (life) or a self membrane (language). These boundaries cultivate a space in which new ideas can land. For more about membranes and the origins of life, read Pier Luigi Luisi’s The emergence of life or David Deamer’s First life. Read my story ‘Wordfall’ on my Grammar for Dreamers blog. For additional content: Subscribe to the monthly Grammar for Dreamers newsletter (and get a copy of the Grammar for Dreamers screenplay). To watch my regularly posted videos of linguistic geekery, follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers or on Facebook: www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ Are you enjoying these episodes? Would you like to hear more? Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google podcasts, or wherever you like to listen. | |||

| 02 Apr 2021 | Teaser for Season 2: Grammar for dreamers | 00:08:13 | |

What’s new in Structured Visions, version 2.0? We’ll still be exploring social structure. We’ll still be geeking out about language. But now I’ll be linking up my discussions to my most recent experiment – combining creative writing with my love of linguistics. Find out more and read ‘Echos and their Others’ at grammarfordreamers.wordpress.com. I’m so glad you’re here! Find me on Twitter: @jodieclarkling And on Instagram: @grammarfordreamers | |||

| 25 Feb 2016 | Episode 33 The Grammar Matrix | 00:32:50 | |

M.A.K. Halliday has this (and a whole lot more) to say about grammar:

In this episode I take the CPU metaphor to new extremes. I claim I’m able to converse with society because I’m just like one of those computer hackers from The Matrix. (‘I don’t even see the code.’) The characters and scenes in The Matrix were formed out of bits of computer code – can we also imagine the characters and scenes of the social world to be made out of bits of grammar? We’d have to imagine grammar as a system, the way Halliday does, and at each level of complexity, a choice is made. Yes or no. One or zero. There are 10 types of people in the world, and at Girl Scout Camp, I became one of the ones who knows binary. Out of all these choices, out of all these possible systemic systemic construals, one gets chosen at each point. Selves get made from sets of choices. Society personifies itself as a character in a context. And then it identifies with that character. And it can’t think outside itself itself. Until something disrupts it. And it has to face itself – as an other – and new possibilities of social structure emerge. | |||

| 29 Mar 2023 | Episode 85 How spooky is language? | 00:48:29 | |

What makes Ouija boards spooky? Is it language? After all, it’s the letters of the alphabet that take up the most space on these devices, and they’re just waiting for something to be spelled out. Who’s doing the spelling? And what kind of spells are they, after all? In this episode we’ll be exploring the occult etymologies of words like ‘spell’ and ‘grammar’. We also examine the spookiness of receiving messages that come without the coordinates of selfhood. As Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou writes, ‘The point of a fish trap is the fish. The point of the word is the idea. Once you’ve got the idea, you can forget the word.’ What if language is a net that shapes itself around an idea to bring it into a different plane of existence? In this episode I share my own spooky idea: that human language is the Earth’s way of creating nets of selfhood from which new ideas emerge. The story I read is ‘My late grandmother’, and it’s available on grammarfordreamers.com. Connect with me (and sign up to my newsletter) here: grammarfordreamers.com/connect Follow me on Instagram @grammarfordreamers, Facebook www.facebook.com/Grammarfordreamers/ or Twitter @jodieclarkling Subscribe on Apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. Rate, review, tell your friends! | |||

| 04 Feb 2016 | Episode 30 Plastic automatons… and other personifications of social structure | 00:35:51 | |

More this week on the idea that social structure might be personified – and embodied. I analyse a conversation between three students whose identities have been challenged in the classroom setting. Their discussion with me reveals that the relationship between individual and society might be seen in a new way. Specifically, how easy does a given social structure make it for an individual to exist as a unique person? The conversation is here: And I also discuss it in my forthcoming book – anyone interested in pre-ordering? | |||

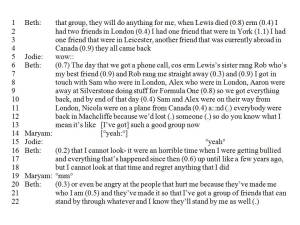

| 12 May 2016 | Episode 44 We got everything back | 00:37:03 | |

Today I explore in a bit more detail these two potentially provocative premises: that the social body is real, and that it hasn’t yet been formed. Let’s take them each in turn:

We can spend all day under the influence of our favourite substances (beer, wine, Haribo sweets) what it means for something to be ‘real’, but for my purposes ‘real’ is useful. If I decide the social body is something that’s real, that I don’t know much about yet, then I get to do research about it with a spirit of curiosity and discovery. Curiosity and discovery are more fun for me than argumentation and debate – though there’s plenty of room for argumentation and debate as well (preferably under the influence of our favourite substances).